A Tale of Two Roadhouses

On masculinity, violence, and Swayzean irreplaceability

For me, Patrick Swayze exists within the bubble of Dirty Dancing. He’s perpetually Johnnie Castle with those wounded eyes and that exaggerated blue collar accent and those mobile hips. Most people remember the bits that made it into cinema immortality: “Nobody puts baby in a corner” and his strong arms making Jennifer Grey look and feel like she’s flying. But I treasure that one brief scene we get of the two lovers playing in the dance studio, before any of the plot could catch them up. Swayze is magnetic with joy in that scene and I have never wanted to see him as anyone else. So I never watched Ghost or Roadhouse and wasn’t prepared to care about the Jake Gyllenhaal remake that Amazon released earlier this year. But one rainy rare day without a basketball game, I allowed my vague interest in Gyllenhaal to lead me to that film, and through that, back to Swayze.

The original Road House from 1989 is a story about violence used in the service of order. In the world of Road House, the state does not hold the monopoly on violence (any sort of police authority is almost entirely absent from the original and is corrupt in the remake). Instead, this is a world (late 80s rural Missouri) where business owners hire strongmen to protect their assets, either in the service of order or in the service of greed and power. Swayze plays Dalton, a self-described “cooler” who has made a career out of going from club to club and effectively organizing bouncers to keep the peace. In the world of Road House people like him are the wandering knights, the cowboys, the Angel-esque drifter. He’s the Marshall from Deadwood; he’s The Mandalorian; he’s Dalton and everyone knows what happens when he turns up.

We first meet him coolly responding to getting slashed with a knife by a drunk patron at his current well-managed club. He is hired away to come fix up a bar frequented by bikers, lowlifes, loose women, and brawlers called the Double Deuce. We quickly come to understand Dalton’s code: he doesn’t start fights and only responds to aggression when he must. He’s polite and quiet; he doesn’t get riled. He respects women and only uses his considerable charm when he meets the right one, ignoring the bare breasts thrown in his direction on a regular basis. He never loses a fight and he does not misuse the power that gives him. It helps he has a degree in philosophy and practices Tai Chi with the patience of a monk. The movie tracks his growing affection for the people associated with the Double Deuce and his growing disgust with local villainous businessman Brad Wesley, who operates like a local mafia boss cum vampire, leeching protection money from every business in town and using his power to exploit the weak.

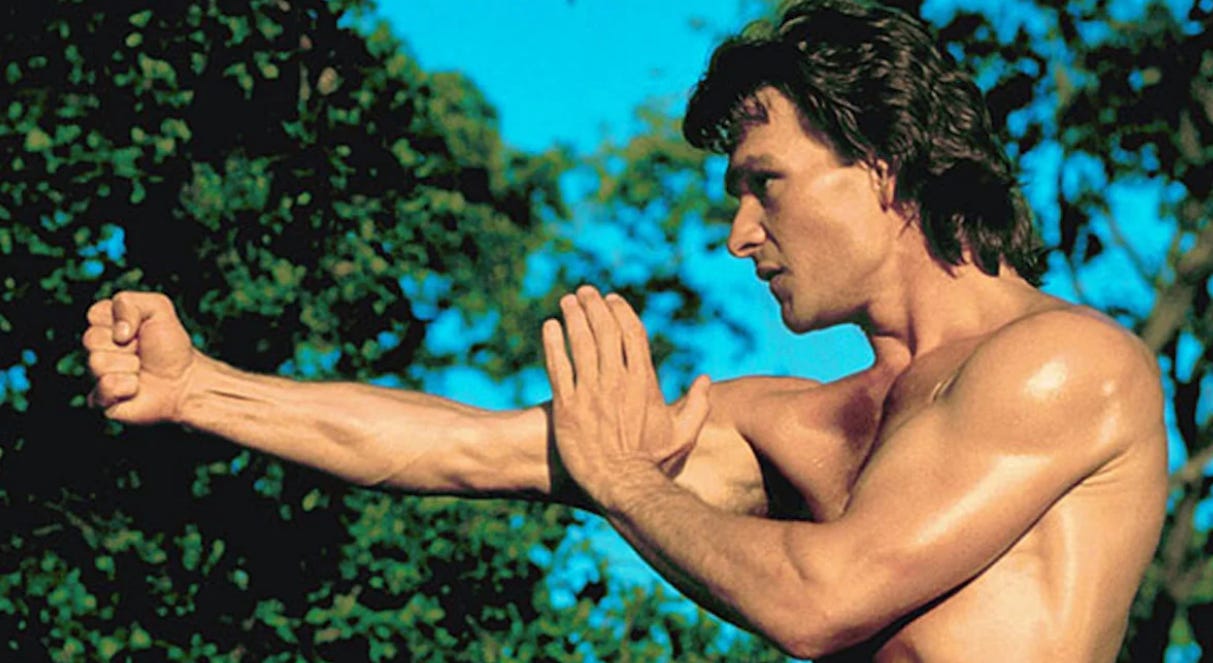

Swayze was wonderfully typecast. In both Dirty Dancing and Roadhouse, Swayze has a tough and unapproachable exterior but when he invites you in, it becomes clear how soft he is on the inside. He’s all mush, a man who wants to believe the world can be a better place but who has been shown again and again what an unforgiving place it can be. Both movies allow him to be emotional and reward him for being more than just a beautiful, deadly body. In both Dirty Dancing and Roadhouse, Swayze is kinetic. His dancing and his fighting are part of the same continuum, and are both about the total control he has over his every muscle. Very few people use their body to act in the way that he does, bringing to mind greats like Jackie Chan and Buster Keaton.

Dirty Dancing was a completely unexpected hit; Roadhouse was a critically panned flop nominated for five Razzies, but emerged over the years as a whole lot of people’s secret favorite movie, including Anthony Bourdain and Billy Murray. So, a cult favorite, but not exactly a well-known classic. In the last decade, there emerged interest in remaking the movie and centering it around MMA, with Nick Cassavetes interested in directing a remake starring Ronda Rousey and Doug Liman finally getting the greenlight to make a version starring Gyllenhaal as an ex-MMA fighter and actual ex-MMA fighter Conor McGregor as his nemesis.

The 1980s was a golden age of professional boxing; Muhammad Ali fought his last fight in ‘81 and Mike Tyson fought his first in ‘85. By 1989, Sugar Ray Leonard is the world Middleweight champion and Tyson is the undisputed world Heavyweight champion. The ‘80s also saw a surge in interest in martial arts, with movies like The Karate Kid (1984), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and Jackie Chan’s Police Story (1985) laying the groundwork for a movie like Road House. Swayze was a trained martial artist and a trained ballet dancer who did all of his own stunts and his characters move with a combination of styles that reflects his own eclectic training. In Road House, Dalton fights like a boxer sometimes and like a martial artist at others, practicing Tai Chi and eschewing weapons unless absolutely necessary. There’s a sense of both responsibility and respect in the way he uses violence, and a beauty too. He made dancing look like fighting and fighting look like dancing.

It was perhaps inevitable that 2024’s Roadhouse would focus on modern MMA, which has roots in older traditions across the globe but owes its modern American incarnation to the 1993 founding of the UFC, a no holds barred competition that encouraged participants to combine many fighting styles and emerge as the ultimate fighter. Since then, MMA has become huge, with C-list celebrity participants like Jake Paul competing alongside true legends like Conor McGregor. MMA spawned Joe Rogan and greenwashed the Saudis. It is woven into pop culture now and it is little wonder that a new fighting movie would focus on MMA rather than boxing or more traditional martial arts. It is little wonder Conor McGregor would show up basically playing a slightly more insane version of his own public persona. But there’s something rotten at the center of this movie (aside from its atrocious plot, acting, writing, and directing) that’s connected to MMA, something strange in the way the movie views it’s own chosen fighting style. Something strange in what it has to say about violence and masculinity.

Outside of more inclusive casting, every change that’s been made in this remake is a change for the worse. It’s now set in the Florida Keys, which is mostly fine but opens us up to the insane number of luxury yacht/speedboat scenes that we now have to endure. While the original movie had no big set pieces, preferring hand to hand combat and no special effects, the new and unimproved Roadhouse has such gems as “Conor McGregor walks into a street market naked and sets it on fire” and “Dalton/Conor crash a speedboat/truck into the Roadhouse,” basically destroying the thing this movie is meant to be about protecting. Many explosions happen and we don’t care about any of them, in stark contrast to the two explosions in the original, both of which happen to destroy places and people Dalton (and the audience) cares about. The violence in this movie is of the bone-crunching variety. Everything is auditory, with little poetry to the movements, partly because so much else is going on you can barely concentrate on the people fighting. While it can be awe-inspiring to watch McGregor fight (if you’re into that kind of thing) because he is genuinely one of the most talented fighters of our age, Gyllenhaal has none of Swayze’s grace and even less of his emotion.

In the original movie, Swayze’s love interest makes it clear late in the film (after he kills a man in self defense in front of her) that the violence he is using scares her and has the potential to turn him into someone as bad as the people he’s fighting. But in the end, the movie rewards Swayze for his use of violence. The villain’s hired muscle all get efficiently dispatched int he final scene, with Swayze killing them one by one as he moves through a mansion looking for the final boss. When he finally confronts Wesley, he chooses not to kill him, thus redeeming him in his girl’s eyes, but then Wesley dies anyway because he lunges at Dalton with a knife and the local businessmen he’s been fleecing shoot him dead. Dalton and his girl then frolic naked in a pond as the credits roll, and we are given a happy ending: Dalton stays and he is rewarded for killing the bad guys he doesn’t care that much about but refusing to kill the one guy who had made it personal. This is all a tad bit clumsy; the ending is probably the weakest part of the movie mainly because Elizabeth (his girl) doesn’t really raise any moral qualms about his use of violence until he takes it too far, in her opinion, but by the time that happens we are so on Dalton’s side that we don’t identify with her concerns. The guy he kills was trying to kill him, bringing out weapons in the middle of a fist fight when Dalton was unarmed. This echoes a story we heard earlier in the film, where he was tried for murder and acquitted since he killed someone in self-defense who pulled a weapon him. But what keeps Dalton’s soul white is the way he uses violence only as a defensive measure. When Wesley is beaten, lying at Dalton’s feet, he doesn’t take it further because he is relying on defensive warfare alone.

In the remake, Conor McGregor says something to Dalton that defines the way the film sees violence. He implies that to be a professional MMA fighter you have to have something wrong with you. That it turns you into someone inhuman, a monster. That you have the be sort of broken to want to be a fighter. This is backed up by what we know about Dalton. His backstory also has a death in it, but in this movie he killed a fellow fighter in the ring because after the guy was down he just kept beating on him until he was restrained. There’s no reason given outside of McGregor’s insinuation that to be good at that sport you have to make yourself inhuman. The Dalton of 1989 would abhor this idea. To fight for sport like that, not to create order or protect the weak, but for money and fame, would be unthinkable to him. To kill a man because you’ve lost control of yourself is exactly what Dalton does not do at the end of the original film, and he has very good reason to hate that man whereas the 2024 Dalton doesn’t even know this guy and has no reason to beat him to death. The end of 2024’s Roadhouse sees Dalton walking away from the bar and his friends and his tepid love interest, punished for the destructive offensive violence he uses when he’s riled. Violence, in this movie, places you beyond the pale even as the filmic logic of the movie celebrates it.

Violence is the reason this movie exists. It’s R rating is entirely based on violence (and Conor McGregor’s naked ass for some reason). It has cast McGregor (and given a cameo to Post Malone (?)) in order to say “look isn’t it cool to watch these guys kick some ass?” And yet, the morality in the movie is at odds with what the cinematography and marketing are telling us. We’re supposed to simultaneously decry violence and think it’s super sick. The movie can’t get past this incoherence; the original film has no such problem. It can reward Dalton for his use of violence because it is comfortable with its own conception of violence, Elizabeth’s minor complaints notwithstanding. At her most effective, she reminds Dalton not to let revenge drive him to forget his own morals, but there is a never a moment when we think Dalton doesn’t have those morals. Gyllenhaal’s Dalton seems just lost in comparison and he ends the movie as he began, a wanderer with no ties. Swayze’s Dalton gets to end the movie holding his girl, in the town he loves, with joy on his face.

It’s worth noting that the reason the 1984 film got an R-rating is more to do with sex and nudity than violence. In that movie, Dalton gets to be a fully sexual man as well as a fighter. He gets to be a lover, too, and some of the best scenes are when he and Elizabeth are sparking off each other. There’s almost as much time dedicated to that in this movie as there is to fight scenes. There’s certainly more time dedicated to building relationships and giving Dalton real ties to the people he’s protecting. Comparatively, the remake is so prudish as to leave me wondering if I’m missing something. There’s one chaste kiss between Dalton and his love interest that comes out of nowhere and is never really followed up on. It feels perfunctory, like the movie required something to check that box but isn’t really interested in it at all. It’s a true loss, because without that this becomes even more of a soulless action flick. After all, if Vin Diesel taught us anything, it’s that these movies should really be about family.

The general sexlessness in this movie is part of a larger trend I want to explore in other posts, but I do just want to hover for a moment on how weird it is to have a big action movie with a heartthrob lead and to cast a character to be his romantic opposite and then just not do anything with all that. There’s plenty of reason to want to move away from the disposable Bond girl, but the Elizabeth character functioned as so much more than that in the original film. She’s a specific at-risk person to focus on. She matters to him and the sex they have in the movie is there to show us a different kind of physicality, a different way Dalton can use his body, a different expression of masculine power. It’s narratively important that she exists and that he frolics in that pond with her and to remove that from the remake is a choice that makes it infinitely poorer.

I’ll acknowledge it is possible to read too much into and write too much about Roadhouse but this remake is paradigmatic to me of some really worrying trends in filmmaking right now. Movies have become bad in a new way, more sterile and paint by numbers, less willing to take risks, and way way less sexy (looking at you season 3 of Bridgerton). It seems very likely that in the years to come fewer movies are going to be made and less risks are going to be taken; this is a bad direction for cinema to go in and movies like 2024’s Roadhouse shouldn’t become the new standard we strive for. According to Google’s new handy AI assistant, who I am naming Reginald after my GPS’s British voice, “The film's estimated budget was $85 million, and it broke records as Amazon's most-watched original movie debut ever, attracting more than 50 million viewers worldwide in its first two weekends.” Yikes!